The two-dimensional art of the Northwest Coast, particularly from the northern tribes, greatly depended upon the audience’s recognition and comprehension of the structure and symbols used by the artist. This was not a decorative endeavor but art produced with a purpose. A design grammar was in place and structural rules were closely followed in composing the design. The artist and his audience mutually understood the design elements involved and thus the meaning expressed by the artist was understood by all. Also, the designs created were connected to family crests and thus controlled by their owners. Not just anyone could design, paint, or display the crest without the rights and privileges associated with it. However, with the great disruptions caused by Euro-American settlement in the region, much of this system of understanding was adversely affected. But it was never lost. In 1965 Bill Holm published Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form and it allowed for non-native enthusiasts of this art the opportunity for comprehension.

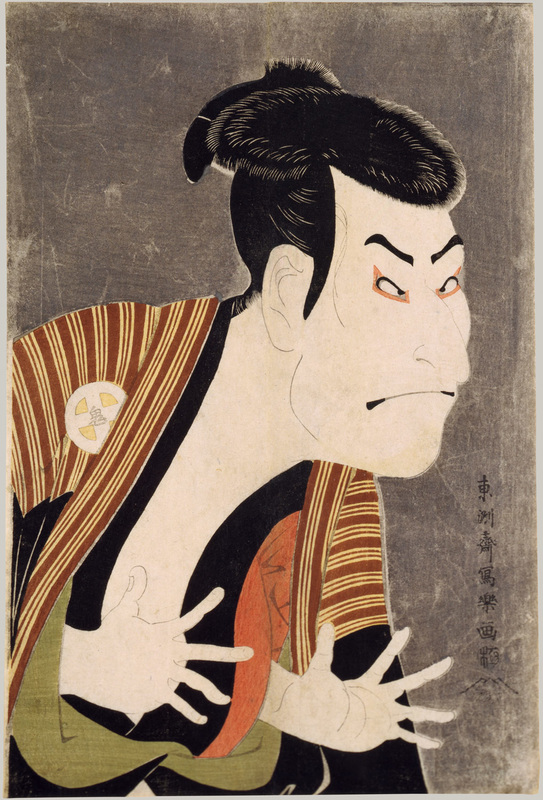

Another example of where the viewer’s prior knowledge allowed them to comprehend the meaning expressed by the artist can be seen in Japanese painting and prints. Both Yamato-e and Rimpa artists used scenes from great literary works The Tale of Genji and The Tale of Ise as the subject matter for their works. Comprehension depended upon the fact that the viewer had either read these novels or at least was strongly familiar with the main incidents in the stories. This allowed artists like Tawaraya Sōtatsu the opportunity to paint a particular scene with just the key elements from the story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed