Today the word “craft” seems to have taken on semi-derogatory undertones, and we have “craft fairs” in opposition to “gallery exhibitions”. It is as if artists need to separate themselves from craft in order to be recognized. This may have recently resulted from the Arts & Crafts Movement’s encouragement of individuals (amateurs, if you prefer) to develop and produce their own personal art, applied or otherwise. In a recent article in Cascadia Weekly, Lummi artists Frank Goes Behind and his wife, Kym, provide the following disclaimer saying the items in their shop were not arts and crafts but work by true artists:

“ Frank and Kym (Frank Goes Behind and his wife) are passionate champions of tribal art and believe the word “craft” should never be associated with the kind of work he and other tribal members produce. “Craft is something you do at day camp,” he says. “What we create is functional art.”

[Quote from “Tribal Images: A Family Affair in Ferndale” by Lauren Kramer in Cascadia Weekly, Issue 6, Volume 11, 2.10.16., p.16]

The fact that these artists must state this shows how much our perception of art still hinges on the Western European ethnocentric view of art and its desire to pigeon-hole and subdivide creative pursuits. In today’s global culture, this amounts to a hold-over of European colonialism.

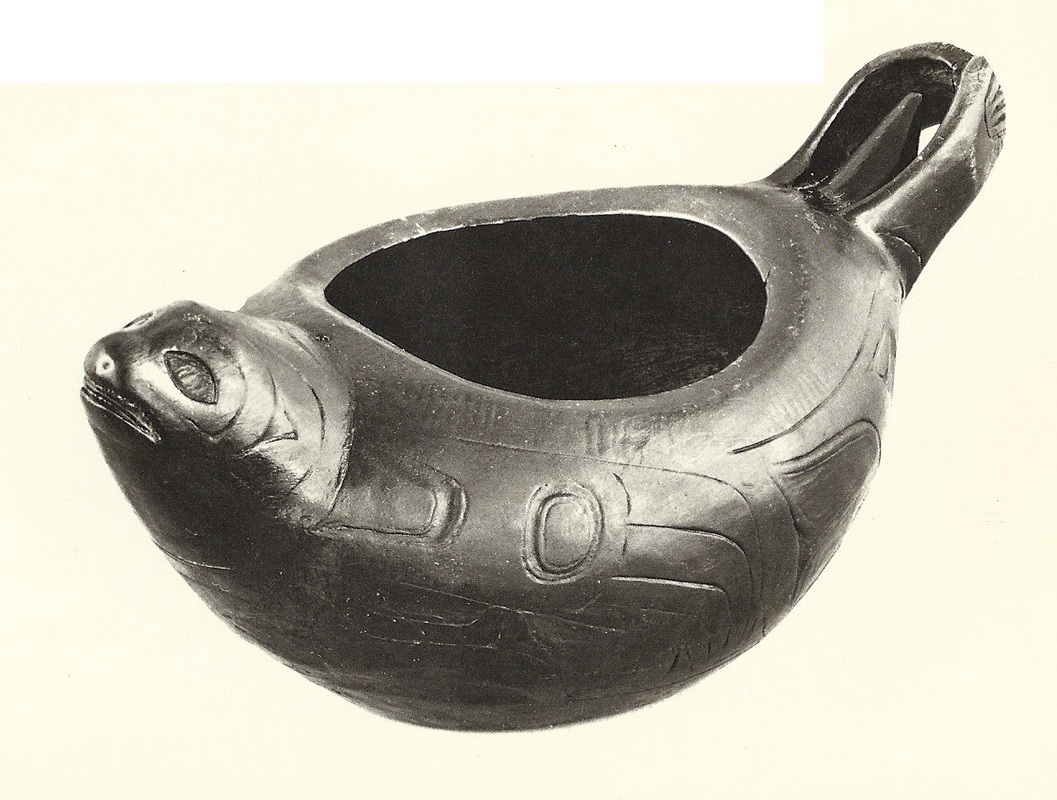

While working at the Ozette Archaeological Site back in the 1970’s, I was able to see firsthand the extent of “decorated” objects in use in a pre-historic Northwest Coast village. Carved items, bentwood boxes, amulets, wall panels, and a multitude of beautifully made baskets came out of just several houses covered and preserved by a mudslide. The art from this small sample of the village was extensive and was not purely decorative but had deep cultural and spiritual meaning to both those who made those artifacts and the ones who owned them. The first Euro-Americans who encountered this art tradition did not understand the significance of the art and lumped it into the broad category of “primitive” art. Since it did not derive from the Western art tradition of fine arts, it was easily relegated to a position of lower relevance and importance (even if admired for its complexity and decorative aspects). Even by the 1970’s this perception still prevailed in the minds of artists/art historians. Bill Holm and Haida master carver Bill Reid addressed this issue in Indian Art of the Northwest Coast: A Dialogue on Craftsmanship and Aesthetics. The following quotes come from their discussion of a carved seal grease dish:

“REID: These objects weren’t merely used at ceremonial affairs. They were treated as art objects, passed from hand to hand, admired, fondled, examined closely. Everyone was a critic and connoisseur. Everyone probably felt some direct relationship with the objects in his immediate family, and maybe even with those in the whole community. These were communities of connoisseurs.

HOLM: No question that’s true. Each piece was made by an individual artist expressing his own style, feeling, etc., and each was recognized as an art object. Must have been. They were made by trained, skilled, talented professionals. A professional artist requires a corresponding audience and a body of critics. Otherwise there really can’t be professional artists—men who produce things desired enough to be commissioned. There had to be this appreciation of art objects—the idea of the object as beautiful, beyond its function, perhaps having a ceremonial role, as well, or expressing rank or prerogative.” (Holm, Bill and Bill Reid, Northwest Coast: A Dialogue on Craftsmanship and Aesthetics, ©1975, page 97).

A beautifully carved grease dish, carved by a master carver following a centuries old artistic tradition, should have the potential to stand on merit alone as a great piece of art. It should not be judged based on an ethnocentric definition of art.

Robert Moes addresses Japan’s lack of distinction between art and craft in his introduction to the book Mingei: Japanese Folk Art. He implies that the Japanese historically regarded artists as craftsmen who product works of art, regardless if the final product is for utilitarian, aesthetic, or religious purposes (or a combination, thereof).

“Before modern times, the Western-style concept of art simply did not exist in Japan. The idea was first introduced by Westerners in 1871.”

“Previously, the Japanese had taken their own arts & crafts for granted, regarding them merely as various skilled trades.”

[Both quotes from Robert Moes in Mingei: Japanese Folk Art, ©1985, page 12]

The reevaluation of the Japanese “decorative arts” began to occur in the mid-1980s with an emphasis on returning to a more Japanese way of considering art. Art historian Tsuji Nobuo redefined the concept of kazari as more than just decoration and ornamentation and as a deeply-rooted cultural paradigm. He states that “the word kazari…has been intimately woven into people’s lives for well over a millennium, and is an integral part of the Japanese language and traditional aesthetics” (Tsuji Nobuo in Kazari: Decoration and Display in Japan, 15th-19th Centuries, ©2002, page 14). Tsuji wrote the forward for the catalogue and, in it, explained how kazari permeates Japanese decorative arts and provides context to design. Thus a beautiful inro maki-e designed by Ogata Korin is as artistically significant as one of his painted folding screens but just on a much smaller scale. Craftsmanship celebrated as equal to artistic vision.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed